This week: Sometimes a word leaves English to travel the world. It grows and discovers new aspects of itself. But coming back home is always an adjustment both for the word and for those of us left behind.

At Tenshon!

There’s a common trope in word-nerd circles that English steals other languages’ words to use as its own and…that’s definitely true. But it’s not the whole truth, which is that other languages steal from English just as much. Because that’s how languages work. All living languages are dynamic and words flow from one to another in many different ways. But it’s never more fun than when they acquire meanings and usages not found in the original language.

We’re used to seeing this in historical contexts; etymologists and lexicographers trace words back through time to figure out where and how it changed. It’s less common to see it happen in real time, but that’s exactly what’s happening with the Japanese word tenshon, or, as you know it, tension.

Tension, as you most likely know, in English is a neutral word in engineering but a negative one in social dynamics. In fact, when we check our old faithful, Merriam-Webster, the first definition given is this:

1a: inner striving, unrest, or imbalance often with physiological indication of emotion

b: a state of latent hostility or opposition between individuals or groups

c: a balance maintained in an artistic work between opposing forces or elements

But, let’s take a look at the definitions given by Jisho (dot org) a popular online English-Japanese dictionary for the word テンション:

1. (emotional) tension; anxiety

2. (highness of) spirits; (good) mood; excitement; energy

One of these things is not like the other. Because tension, in English, is not used in the manner that definition 2 suggests. In other words, in English, “Let’s raise the tension,” does not equate to “let’s get this party started.”

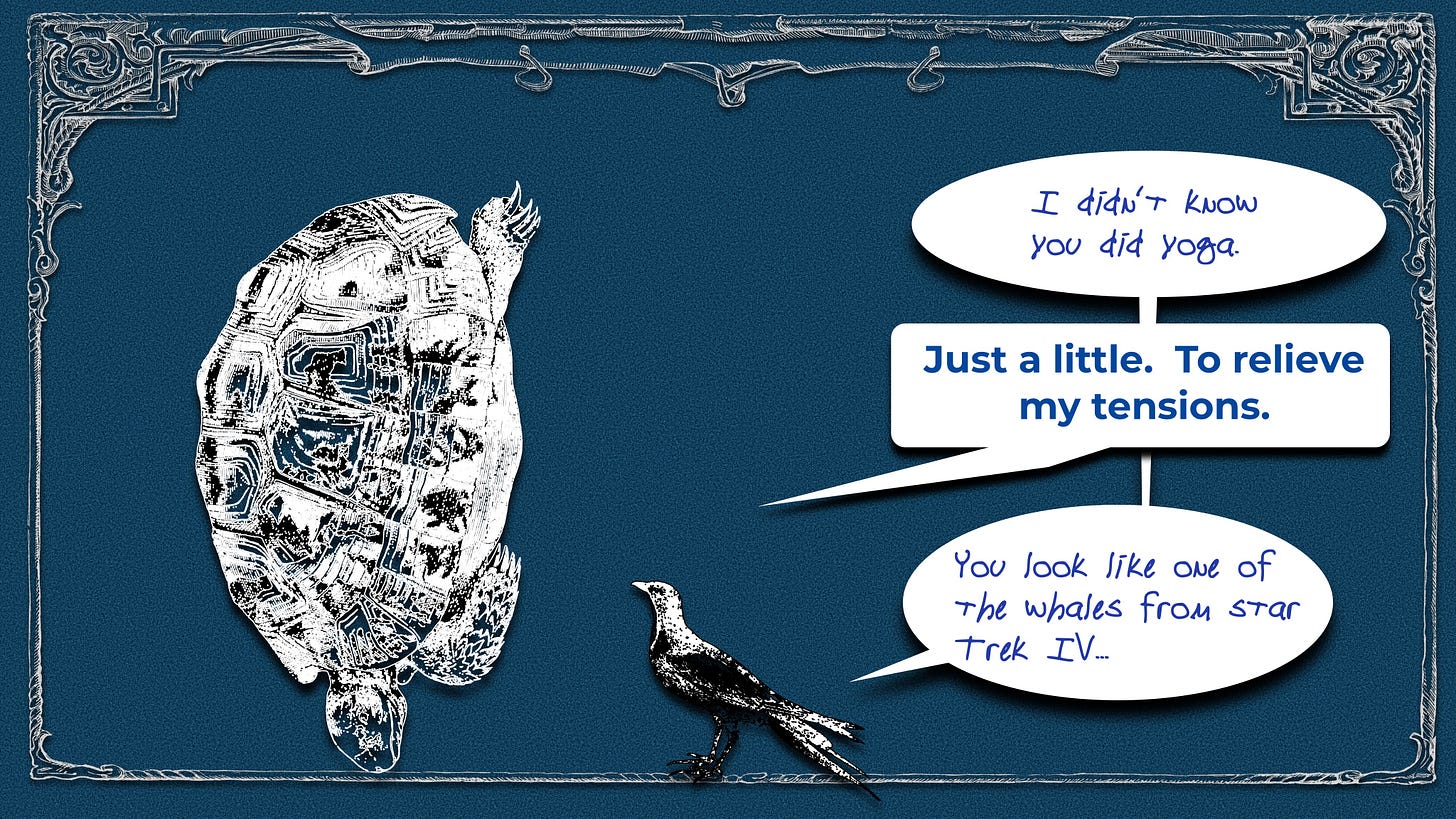

Here’s what I mean - one student of mine likes to tease me by giving me updates about the state of the class. So, for example, when I make a pun that she has deemed “off,” she’ll tell me, Sensei, tenshon sagaru. Literally, the tension is lowering.

Now, again, in English, lowering the tension is a good thing, right? It means to defuse a stressful situation or to calm down. And yet, my student’s meaning is immediate countered by the (vanishingly) rare times I make a joke that meets with her approval: Tenshon agaru! The tension is rising1!

The problem, of course, is that we can see where this usage might cause problems for people coming to Japan who are not yet familiar with the language. Not to mention the trouble a student might get into if they took the Japanese usage of tenshon with them to an American school.

But it makes sense, doesn’t it? If something can be raised, it can be lowered and it tension can be applied, it can also be released, so why shouldn’t the metaphorical usage of tension work in the same manner? Isn’t this how language works?

Yes, and no. Tension’s history traces back to a latin word for stretching. By the mid-1700s it had become a metaphor for stress and anxiety. From there, derivatives and nuances came along at a steady pace, giving tension its modern usages across physics, art, music, and psychology. So adding a meaning to the list is not an unreasonable idea.

But these changes take time and have to occur naturally. I like the idea that raising the tension of a room means that you’re bringing up the ambient excitement level. I think it works on a few different levels. I also have to mark it wrong on my students’ work.

Being a second-language teacher is a delicate balance between letting students play with language and telling them how the language works right now. Students need to engage with and work with their target language until they own it and feel comfortable using it to express themselves. Teachers, on the other hand, need to let students know what is and is not appropriate, which, in this case means telling students that they are not expressing the thought they wish to convey by using a particular word. Which really lowers the tension.

Fortunately, language is fluid. What we can do is help students and learners find ways to give context and explanation to new phrases and twists on their target language and get that tension back on the rise.

Down the Rabbit Hole

Not so much a rabbit hole this week as just a book recommendation. My daughter and I have been working our way through How to Draw Adorable by Carlianne Tipsey2 and it is just what it says on the tin - a bunch of tips and tricks on how to draw adorably cute characters and, in fact, how to turn any random object into a cute character.

I’m finding it a fun refresher on a bunch of drawing and cartooning techniques, but the real joy for me is watching my kid (who’s eight) make her way through the book, her eyes bright and pen busy as she learns each exercise.

From the Archives

Since I mentioned that puns are often what causes tenshon to be lowered or raised in my classroom, I thought we might oughta look back at just what puns are. Fortunately, I covered this a while back in the issue linked below. Go read!

Technically, this should be tenshon ga agaru, which Jisho actually lists as an idiom meaning, “to get excited; to get hyped up; to become happy; to get in a good mood.”

This link goes to my store on Bookshop.org, meaning that if you buy it through this link I’ll get a few cents commission.